A NEW KIND OF GOLD MINING

TEXT JOSEPH TEELING

ARTIST BEA FREMDERMAN EXPOUNDS UPON HER LATEST SOLO SHOW IN LOS ANGELES: AN EXPLORATION OF WEALTH, TRADITION, AND COMMUNICATION TODAY

Bea Fremderman is an artist living in New York. Her show Hindsight is 20/20 is currently on view at Aran Cravey Gallery in Los Angeles. She has shown internationally since 2007 in spaces including the New Museum, Rhizome, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. The show in L.A. is a witty floor plan of dark humor and despair. Formally seductive multidisciplinary works address overproduction, value and waste, leading the viewer through the titles (all based on old Russian proverbs) to the objects ranging from prints and concrete sculpture, to Eastern Bloc wool boots and chicken coops. Fremderman manages to keep us smiling, if somewhat uneasily, while we contemplate the relative nature of value.

Can you pick three pieces from the show and describe their production and content?

BEA FREMDERMAN Untitled (drawing): This is my favorite piece. It’s the last piece you see in the show because it is hung on the back of the chicken coop, which is in the back of the gallery. I wish I was a better draftsman, but I’m not. I had a vision for this piece and originally I was trying to figure out a way I could produce this work myself. I was toying around with the idea of making a 3-D rendering (which I can do), but it honestly didn’t feel right. I wanted something a bit more intimate and human. Also something that the viewer knew took time. I sketched out a few ideas and presented them to a friend who was commissioned to execute the piece. I have a day job. I need to have a day job in order to pay my bills. I love my job because it allows me to do what I’m really passionate about in life and that is a great thing. Most of us don’t feel like ourselves at work. We do what we’re supposed to in order to pay the bills, afford the things in life that make us a bit happier and enjoy the company of others over an overpriced glass of wine. Jobs allow us to leisure. In leisure time, we finally connect to our true selves and no longer feel disassociated from who we feel we are. The drawing is an objectified version of myself. A box figure in the heterotopic confines of an ambiguous elevator. The setting is similar to an office or bureaucratic setting. In my hand is a cellphone and a credit card. The figure is staring directly at the viewer with a Mona Lisa-esque gaze.

Untitled (Bench): The idea for the bench actually came to me in a dream. It’s very unusual for me to remember my dreams, but as soon as I woke up I quickly sketched out the divided bench I had dreamt up, at four in the morning. The design is familiar but strange, not only because of the bird spikes but also because of the brutality of the design itself. A divided bench like that is usually found in public spaces. At bus stops, outside of corporate high rises, etc. Usually, division benches try to hide the fact they aren’t permitting someone to lay down. At first glance those benches seem harmless. Almost polite in a way, like they are breaking up space so you don’t have to touch the person sitting next to you, sterilizing the space in between individuals. The reality of the bench’s design is that it keeps people from truly resting.

Hungry Bellies Have No Ears (gold scrap, bar and tooth): The pieces of gold scrap from discarded electronics are reappropriated and coalesced into a functioning part of the body, the ersatz tooth, which resides in the main faculty for communication in the human body. So you have discarded currency of information, contemporary gold panning through flow of discarded technological ephemera...Something I always find myself thinking about is how in 1971 the US went off the gold standard. That value in regards to US currency became a concept and something to be interpreted. Equally as interesting to me is panning for gold. That out of nothing you can find something, that in dirt there’s value. Now there’s a new kind of gold mining that consists of recovering gold from electronics. It’s crazy the amount of obsolete electronics everyone owns. My parents for example have a huge stack of old VCR and DVD players in their master bedroom. I know that in my room they repurposed one of my underwear drawers as an old cellphone drawer. I don’t think they have enough time to go to the recycling center, so everything just kind of gathers in the house. Most of our computerized electronics contain gold because gold is a conductor of electricity. Hungry Bellies Have No Ears is a sculptural triptych consisting of three acrylic boxes held together with gold screws. The first of the three boxes is filled with miscellaneous electronic scrap that contains gold conductor bits. The second contains an impure gold bar that was melted down from all the bits. And the third contains a pure gold crown tooth. The idea was, something that was once obsolete is now functional again because of the integral property of gold. The gold goes from a transmitter of electronic information, to a material, to a functional part of the body that also transmits information.

STAGES OF LAUGHTER

by Kate Berlant, Aki Sasamoto, Amy Sillman, Martine Syms

June 1, 2015

Martine Syms- HOLLYWOOD ONCE HAD a near monopoly on the manufacture of celebrity. Showbiz took unknown New Yorkers like Leonard Schneider and turned them into Lenny Bruce. Now, anyone can create a marketable persona using the extended narratives that flow through social media feeds. The rising popularity of contemporary art has redefined what it means to be an “art star.” Fame is dependent on an outsize number of followers. Artists are modeling their self-presentation after comedians and small-screen celebs.

I’m thinking about Amalia Ulman’s performance Excellences & Perfections (2014), which took place primarily on Instagram. Over the course of five months, Ulman posted a series of carefully staged images conveying the fragmented story of a young woman who, like Tina Fey’s Liz Lemon, struggles with the four basic guilt groups of food, love, work and family. Unlike Lemon, Ulman transformed herself (or at least her image) through diet, costuming and postproduction. She conducted extensive research on the verbal and visual language of three female archetypes, which she described in a recent interview as “the Tumblr girl (an Urban Outfitters type); the sugar-baby ghetto girl; and the girl next door, someone like Miranda Kerr, who’s healthy and into yoga.”

Ulman embodies these girls in her images and endows them with the semblance of personalities through captions. Excellences traffics in the tone-deaf language of hyper-privilege. Ulman, in the guise of one character, rapidly shifts from the ecstasy of consumerism to callous vanity. “Matching!! #flowers #girl #iPhone #nails #sunglasses #dolcegabbana #dolce&gabbana,” reads the caption of one selfie. Another—a sexy full-body shot—lists “reasons i wanna look good.” (On the list: “To plant the seed of envy in other bitch’s hearts.”)

I didn’t pay attention to the project, until Ulman described it in the interview as a romantic comedy. The main tropes of that genre are ripe for creative mutation. When done right, romantic comedies articulate our unspeakable desires of all kinds, whether that desire is for affection, objects, happiness or an identity; the worst rom-coms are merely about falling in love with someone.

I’ve long harbored a secret dream to create a half-hour comedy-drama with a strong female lead. In my fantasy, the working title is “She Mad.” The phrase has become a Hail Mary to diffuse ridiculous arguments about cooking and cleaning in my household. I used to say, “We’re not in a fucking sitcom!” Now I say, “She mad,” and it’s like we are.

Earlier this year I made a video called A Pilot for a Show About Nowhere that considers the politics of watching television. It’s about the way I frame my life within the fictional milestones I learned from pop culture. Should I be anxious that I don’t have a car or a house or a job? I’ve described the project as an experimental sitcom pilot, though it doesn’t resemble a conventional episode in any way. I appear in filmed reenactments of my daily life, and a “She Mad” title card is used occasionally to suggest a complete, linear narrative. When I showed the video to a friend who works in the industry, he told me that if I wanted to “be like Steve McQueen”—as in, break into the mainstream from the art world—I should “pull a Lena Dunham.”

In artist and writer David Robbins’s book High Entertainment(2009), there is a chapter on self-presentation and impression management that includes two memorandums. “1. Imagine what a system, context or culture needs. 2. Be that thing, either through real actions or by creation of a persona.” Ulman turned into a hot babe, took the lead role in her own drama, and earned herself thousands of followers from within the art world and beyond. Though the format she used may be new, the basic characters Ulman deployed to explore female desires and insecurities have deep roots that extend to the earliest forms of popular entertainment.

On another level, art careers can resemble episodic stories, with meaning accumulating, narratives developing and clout building from exhibition to exhibition. Ulman figured out that she could control that storyline, too, by casting herself in any role she wanted.

There’s also evidence that the art system is hungry for qualities associated with another type of comedic performer: the stand-up. Matthew Daube, a Stanford researcher whose work focuses on the performance of race and comedy, suggests the stand-up comic as a desirable model for contemporary selfhood. This individual can “operate amidst apparent entropy with the security of an ironic outlook.” The best way to reveal silent expectations or scrutinize and subvert assumptions is with a joke. Comics are highly attuned to the relationship they establish with their audience. “It is against and with the audience that the stand-up comic stands up, simultaneously one of the crowd and yet distinct from it,” writes Daube. Many artists use this double-consciousness to their advantage.

One art wit I’m quite envious of is Yung Jake, né Jake Patterson. He’s a Net artist, a rapper, a creative at Cartoon Network and a director of both Pepsi commercials and music videos for the cult hip-hop act Rae Sremmurd. Yung Jake was born on the Internet in 2011. The songs he produces are three-minute bits usually accompanied by online videos. In “Datamosh” he brags about his digital effect skills in a glitched video. The lyrics annotate the images. “I’m moshing data, making art on my computer.” Jake once left a comment on the site Genius.com explicating his own self-referential work: “Yung Jake is calling attention to the fact that his videos are ‘art.’” In “E.m-bed.de/d,” Jake goes viral, creating a feedback loop in a narrative that spans multiple browser windows. In a recent live performance of “Look” he stood between a laptop and a dual projection of his desktop and iPhone screens. He spoke to the audience and into his devices’ cameras simultaneously. A text message to his phone was all it took for the audience to become a part of his show, their words appearing live onscreen. Most of the messages he received were nonsense.

The joke as we know it is a modern invention that arose from vaudeville. Cultural historian Susan Smulyan argues that the “compression and verbal basis” of Jewish humor made it perfect for mass media. Black humor thrives on the Internet. In the black vernacular tradition, words, signs and their meanings can be endlessly doubled. Scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. likens the effect to a hall of mirrors. This fluidity of language is what Internet memes are made of.

Take Los Angeles artist Devin Kenny. (Please, take him.) He spends a lot of time on his computer when he’s not making sculptures, videos, installations and music. I first encountered him on Facebook and I couldn’t remember if we were friends in real life. When we finally met it didn’t matter. We’d shared so many links at that point. Kenny uses words out of place. A few years ago he installed status updates/jokes on the marquee of a theater in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. My favorite reads: “Twerkin’ is shorthand for gesamtkunstwerkin’.”

For “Wrong Window,” his exhibition at Los Angeles’s Aran Cravey Gallery, he made an Internet of things. Untitled (But I swear this beat go haaard), 2012, is a glass plank on which the parenthetical title has been rendered in enamel. It’s a comment made physical, and it’s installed in a group of similar works adorned with verbal asides and emoticons. Another piece called Slave name/stage name/Ellis Island snafu (2008/2012) lists possible names for his alter egos. Kenny raps under the pseudonym Devin KKenny. His raps are funny because they’re true. In interviews he notes his interest in the figure of the griot, a traditional African historian who speaks in musical, poetic language. His latest track, “LANyards,” ends on a refrain that speaks to the plethora of social media services offered gratis: “If it’s free, best believe you are the product.”

Paradoxically, you might be able to avoid being the product by becoming one. Nathaniel Donnett has a 2011 sculpture titled How Can You Love Me and Hate Me at the Same Time?, a protest sign modeled after those held at the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike declaring, “I Am A Man.” This one reads, “I AM A MEME.” The original was a declaration of independence. Expressing pride at being a meme means establishing a link between personhood and the representation of a person. Self-reference is salvation from top-down control.

#studio #visit with #devin #kenny

by Barnett Cohen

April 24, 2015

It’s fitting that my conversation with artist Devin Kenny occurred over email. Kenny is constantly utilizing or referencing the internet; through his tumblr Studio Workout, his heavy presence on social media (Facebook/Instagram/Twitter), and through his art practice. His “objects of regard”—otherwise known as sculptures for those who are uninitiated to Kenny’s comprehensive mnemonic devices—at his recent show at Aran Cravey, circled back to the computer. His simple wood sculptures, titled Desktop Widgets, resemble our collective tools for accessing the internet: i.e. mice, iPads, hard-drives. In our computer- screen-mediated conversation, we began by discussing Kenny’s relationship to the internet and wound up touching upon hip hop, comedians, and kicks.

Barnett Cohen: In your interview with the artist Brad Troemel, you said, “the interesting thing about using the internet is that it is a space that in some ways is an analog to the way my mind works.” Speak more on that and how the rabbit-hole that is the internet mirrors your mental process?

Devin Kenny: I’m excited by through- lines of connection. I often link things together like a web, point-to-point, from the outside in. From skateboard- ing and graffiti, and growing up in this beautiful Black body in a very segre- gated city, I became very aware of my environment. I love hip hop, and its concern with chronicling life at street level; and through it I felt supported in my passion for the visual and auditory culture I would encounter on a day-to-day basis. My subcultural interests were fostered by the internet, whether it was p2p or bulletin boards. There’s also the aggressiveness and the detritus of the internet: pop-up ads, banner graphics, spam threats, chain letters, away messages, avatar signa- tures. All these things seemed rife for the same attention and appreciation that I would give to what I passed on the street or on public transportation.

As a teen online in the early 2000s, I had this painful feeling that all this cool stuff had happened in the past, and that I just missed the boat—and that it would never return because the Patriot Act was killing everything. Maybe this fear was a result of an overexposure to materials; I used to borrow like seven CDs a week from my older friend Dorian. He had a huge library (multiple walls of tapes and CDs, graphic novels, incendiary literature, etc.), but even that paled in comparison to how deep I could plunge online.

BC: How attached are you to the words you employ within your work? So much of our contemporary inter- action with language and images is fleeting (i.e. scrolling through Instagram or our FB feeds) and I am curious if/how that interaction or relationship impacts your work?

DK: Was I a man dreaming I was a Snapchat or a Snapchat dreaming I was a man...

My Instagram is pretty light on text, which is fun for me. The Twitter and Facebook accounts are a differ- ent story. I think a lot can be pulled out of a thing meant to be looked at only briefly; that which is discarded can often have a kind value which is not acknowledged or engaged. I like the rapidity that’s possible with social networking and I sometimes seek to bring that kind of immediacy into the art I share with people in physical space. I am also interested in the kind of slowed time possible when you’re in a space full of “objects of regard”.

BC: I find a large chunk of your work to be delightfully tongue-in-cheek and I am wondering if you could speak to your attachment to the objects specifically. Your particular use of humor and your personal investment in the work seem to operate in tandem. For example, the photocopied images that you exhibited at Aran Cravey had a disposable quality to them that struck me as purposefully out-of-place in the setting of a commercial gallery.

DK: The photos were originally part of a double-sided installation in the Made In LA show at The Hammer last year. They were 35mm range- finder photos I took in Culver City, Inglewood, and other parts of L.A. They were then scanned and printed on an office copier and pinned to a cubicle wall. They resist some of the restrictions of the curated print while also letting a person take in the image. It’s not about fighting ‘the pre- cious’ as a rule, but it is about giving opportunities [for interaction] that isn’t always available to people. A lot of work in the Aran Cravey show can be touched by people (the yoga mat/ mouse pad, the masks to wear for ris- qué selfies, and the widgets), because OPTICAL ZOOM IS NOT ENOUGH!

BC: Does the act of titling function as a kind of finale for you to the act of creation?

DK: I usually name pieces at the end, and I just try to have fun in the ways

I know how. I do try to make the titles and the works “rhyme” with each oth- er somehow, even if it’s a slant rhyme. It was a long time before I could embody some of Yeezy’s teachings.

BC: How did you arrive at the vari- ous alternative personas you have created, like Devin KKenny, Darren Krutze, and Ellsworth R. Kelly?

DK: Devin Kenny came from a satire about how there weren’t a lot of MCs who used their real name (Kanye West, Erick Sermon, and Mike Jones being the only exceptions at the time, though this has changed). It started as a performance art/music project jumping off of an imagined meeting of the South Bronx (hiphop) and Downtown (art). That and how your name always gets misspelled before you’re famous.

Darren Krutze is from a project that was in the show at Aran Cravey: a photo diptych titled, Slave Name/ Stage Name/Ellis Island Snafu. I was thinking about the given name as an ideological container and the violence of “making things easier for people.” Whether it be a stage name chosen to evade/delay anti-Semitism, or remov- ing diacritical marks, and the cultural mismatches that arise from the legacy of slavery. The photographs are of a wall that was a shared studio space at Cooper Union where I started writing this list of names that were “ethnically consistent” (culled from baby name websites). The caveat was that they all were names that become “D.K.” I wrote them with a fat tipped marker (graffiti reference) and even- tually people picked up on the pattern and felt entitled to contribute to it so there’s a degree of social construction going on too.

And Ellsworth R. Kelly, I mean, you know how you can get real nasty with abstraction, right? My sister went to junior high with Kellz.

BC: I recently saw Jerrod Carmi- chael perform a set at the Comedy Store. He said that he feels like he is compensating, always compen- sating. Like he buys boxes of kicks, of sneakers, to compensate for growing up poor. On your tumblr, Studio Workout, you posted a photo of a sneaker (JS Wings 3.0 designed by Jeremy Scott and fabricated by Adidas) with the caption “sculptures on my feet, haters on my heels, emptiness in my heart.” It reminded me of Carmichael’s bit.

DK: I started Studio Workout in 2010 to unpack why so many people I knew would be blasting Trap music, or Dipset, or other epic music about drug dealing in their studios. Both volumes of the Studio Workout mixtapes deal with the intersections of the heroic white male painter, and the hyper-masculine Machiavellian Black male rapper, who is portrayed as heartless and subhuman. Studio Workout is a performative space and many of the posts are from a figure who’s a mix of these two archetypes. In regards to compensating, when you are told from all angles that you aren’t worth anything, and that you’re unlikely to amount to anything, for generations on end, the desire to stunt on people can becomevery strong.

BC: LOL on the heartless and sub- human heroic white male painter.

DK: Ha! I didn’t actually say that but it’s funny you put it that way. The thing about archetypes is one may feel left out if one don’t easily fit into them. The other thing about arche- types they can be very lucrative for people. Shout out to George Lucas.

Devin Kenny at Aran Cravey

March 10, 2015

For a show that’s largely about Internet culture, Devin Kenny’s exhibition at Aran Cravey is surprisingly tactile.

The artist, lately of L.A. now living in New York, skewers the foibles of online and high-tech culture, focusing on its implications for physical interaction.

On entering the gallery, the viewer is greeted by a plain wooden table, about the size of a desk, on which are arrayed a number of small, variously shaped wooden objects. The items, some rough, others smooth, are oddly familiar yet hard to place.

It turns out they are dumb, perhaps Platonic equivalents for everyday desktop items: mouse, mouse pad, wrist rest, etc. The viewer is invited to touch and manipulate them, highlighting the limited spatial range of a lifestyle tethered to a desk.

Corporate culture is parodied more explicitly in the music video “LANyards,” in which a team of multiracial young people meets in a bright white conference room to pore enthusiastically over complex flowcharts, eat healthful snacks and high-five one another. For anyone who’s ever worked in the “new economy,” the spoof will ring hilariously true, as does the accompanying lyric, “You are the product.”

Other works explore the tension between top-down control and emergent countercultures. A horizontal stripe at the top of one wall is painted in bright pink, anti-climb paint, which never dries, creating a slippery surface resistant to intruders and graffiti.

At the other end of the spectrum, Kenny has coated inkjet prints with frit, a sharp, ceramic sand. Used by those who put up unsanctioned postings, it makes the posters actually painful to remove. These very blunt, physical methods of control parallel the Web’s two-faced promise of free expression and invasive surveillance and marketing.

The content of Kenny’s inkjet posters also plays with these themes, alternating between faux advertisements for bands and inspirational sayings. The band posters at first appear like lists of gibberish culled from the Web — “HYPERDRUNKALWAYS,” “IRONIC PAN.” These are recast as band names with the addition of a cheeky, handwritten “All Ages!” The posters poke fun at the proliferation of nonsensical group names but also at the Internet as a babble-generating machine.

By contrast, the inspirational sayings are texts about religious belief and perseverance that you might find cross-stitched on a pillow. Here they are overlaid with degraded images of tacos, pizza and soft-serve cones: junk food for the body and the mind.

The connection between virtual and physical worlds is made still more explicit in the video, “Swipe right on ’em all and let G-d sort ’em out…” It consists of sequential close-ups of a thumb making a familiar swiping motion across a fistful of dollar bills, a smooth stone, and a smartphone screen displaying profile pictures from the dating site Tinder.

The video highlights a simple, repetitive gesture whose significance has grown exponentially. With complex information easily manipulated with the casual flick of a finger, our mental, emotional and social lives come down to the edge of a digit.

“Wrong Window” by Devin Kenny at Aran Cravey, Los Angeles

By Yanyan Huang

Devin Kenny’s “Wrong Window” presents nuances of everyday violence that underlie present-day social interactions and the intentions behind them, good or bad. He simultaneously embraces and rejects institutionalized and systemized tropes, including “social media” applications and intermediary devices, consumer technology, education, corporate culture, and everyday interactions.

“Swipe right on ‘em all and let G-d sort ‘em out” is a short video underscored by a tranquilizing loop of an upbeat and generic Muzak composition paired with an equally repetitive video diary of everyday activities that are comfortingly familiar but ultimately unfulfilling: swiping on Tinder, counting dollar bills at the ATM, rubbing the smooth surface of a found pebble, or a “worry stone”. As it loops endlessly, one realizes that days are made up of such enormous amounts of inanities and errands. Days add up to years, and years add up to a lifetime of banality. What was a placid daily activity account becomes either horrifying or calming, based on each individual viewer’s degree of knowledge regarding eastern religious philosophy.

“Prominently Displayed” is a series of text work divided into two categories: nonsensical internet word mashups similar to automatic writing without the necessary language key, and mindlessly positive phrases, saccharine while poisonous, like so many things that are marketed to us daily. Phrases we recognize as an everyday repackaging of misery: “Life is too short to wake up in the morning with regrets. So love the people who treat you right. Forgive the ones who don’t. And believe everything happens for a reason”. “Life is too short to argue and fight. Count your blessings. Love the friends and family that are always there. Smile more often. Make the most of everyday”. If taken at face value, these phrases of advice might have been tenderly and carefully stitched onto cross-stitch pillows and quilts and framed in the heyday of arts and crafts and home economics classes. In 2015 however, we don’t know how to make use of such saccharine positivity and generally regard all messages with a suspicious mind, whether positive or negative. “Are you for real?” or “lol jk” can follow any statement to immediately distance the speaker from his speech-act, like a built-in safety cushion. Eager to not offend, people speak half-heartedly in half-jokes in every area of social interaction that was once guided by principles of sincerity. But if everything is funny, nothing is funny. If nothing is serious, what are we left with?

“LANyards” is a music video featuring the artist’s own composition and showing educated, multicultural, young bright employees who fit the mold of the 2015 technology/advertising/marketing/design creative mold, cooperating and thriving in generically “cool” loft-space offices with an open plan and bright, natural light. The set calls to mind offices of venture capitalist-funded Silicon valley backed tech companies: apps, services, programs. We see people discussing, making plans, laying down strategies – for what purpose we never learn. But corporate positivity is palpable and alluring as ever. Surely they must be working for the benefit of the consumer today, for all of humanity today. Viewers would love to be there at that control room, being “on the ground floor”, being part of the “decision making process”, “being a part of it all”, joining in on the (unnamed and as-of-yet purposeless) positivity and excitement.

Two commonplace consumer product sculptures are displayed on pedestals: “VHS Mop”, a magic eraser-type of contraption repurposing an outdated artifact of technology that once had enormous use, has one end covered with a dry-erase board eraser material. Dry erase boards themselves are becoming obsolete as computers and powerpoint presentations have already replaced archaic instruments and habits of communication: writing, erasing, watching, rewinding, taping over, fast-forwarding. With the rise of DVDs and internet streaming services, the downfall and bankruptcy of VHS-lending giant Blockbuster shows the speed and violence with which new technology can destroy previously useful ideas, as well as the ever-present pressure to jump aboard perpetually newer ships.

“Worksheets”, a 90’s white and purple child’s laptop/“fun learning device” sits on the other pedestal, its functions long abandoned, usefulness long forgotten. The space around the minuscule screen has been covered with chalkboard paint and scribbled on with chalk. Overlaying a once-cutting-edge, now obsolete technological instructional device with a fast-disappearing traditional method of institutional instruction imparts upon the viewer twinges of nostalgia for a childhood full of tactile experiences. Rare is the childhood memory that doesn’t include blackboards, chalk that broke easily into pieces, drawing on asphalt, chalk powder left on fingers and palms. We’re left with a forlorn sense that tradition sometimes trumps innovation, that simplicity sometimes trumps complex technology. Not too long ago, people relied on little more than their imagination and books to keep themselves entertained and curious. Having long abandoned this self-generating practice of self-inspiration, we endlessly consume and discard hugely profitable created needs in a cycle too well-worn to imagine alternatives.

“Untitled (hourglass widget)” features a custom wooden table covered with a collection of pieces of wood scavenged from the workshop where Kenny works part-time in New York. They have been carefully shaped into human-sized shapes, resembling wooden blocks a child might play with. One side of each is dyed with an industrial color commonly found in consumer food products, especially in candies and cereals for kids: Red 40, Yellow 5, Blue 1, Blue 2, etc. Such dyes are used extensively in M&Ms and in cereals marketed to children and have been widely known to cause neurological disorders and behavioral problems. Before the mass commercialization of foods in the 50s, food manufacturers used to use natural plant and vegetable compounds to color their products. With increased production and lowered standards of safety common in production-line food processing, petroleum-based dyes were introduced as a cheaper alternative. Like anything else we are pressured to desire and buy and consume, it’s actively harming our brains, bodies, and generally trying to kill us. (American Journal of Psychiatry, 135:987-988, 1978, A Crossover Study Of Artificial Food Coloring In A Hyperkinetic Child).

A spotless museum-quality display table shows several groupings of “widgets” under clear glass. “Uniform Code Switch B” shows a clear PVC kid-sized backpack stuffed with a yellow toy gun in a meticulously displayed museum-quality glass table. The table itself acts a barrier to the objects, making the viewer look at them in a purely aesthetic or art-theoretical manner. It sits next to wifi symbol stickers, “Turn pro next year”, bubbled industrial acrylic “Selfie masks”, stone props from the “Hold onto your memory” video, brass strips that imitate VIP wristbands and hospital bracelets “Access”, and a temporary tattoo, “Prince’s side-eye”. The assembled objects seem to be a starter kit of political subversion, a joke of a protest against the powers that be seeped in despair – the last rebellion cry of the hopeless – “This is what you expect from me, so I’ll give it to you – but just know that I know that you know that I know, and we can continue this dance of gains and reversals, appeasement and hostility ad infinitum.

“Right around the corner” is a laminated newspaper article of kids in Chicago making predictions for the 21st century. It shows the artist as a precocious sixth grader, expressing a hope for stricter laws and an intercontinental government in the future, or the world could be faced with the problem of “an android robbing the bank”. Seven years after the global financial meltdown caused by high-frequency speculative trading and global offshore tax evasion gone haywire, precisely what the young artist wanted all those years ago could have saved us from the current extended recession. These wishes that have not yet come to pass hang on a wall adjacent to the artist’s present: a present where his imagined not-so-distant future has not really measured up to his hopes, but more likely, has grossly failed to even live up to his worst fears, and continues to disappoint him – history managing to rudely cut across time and recall civil rights and human rights advancements. The idea that time brings progress is a sad illusion. Progress is not bound by time and has no need for time. Progress can happen at any moment with the enlightenment and involvement of people at the individual level. To relegate progress to a flippant “time will take care of it” is grossly irresponsible and insensitive to people who have the least amount of time.

Humans for all their “progress” and “expansion” and “gains” still destroy one another through the most positive false intentions and jokingly mellow rejections. Soft violence is still violence, and it pervades our lives in insidious and nearly invisible ways. Service with a smile, and nothing more.

MARCO KANE BRAUNSCHWEILER

Aran Cravey Gallery

Working out of downtown Los Angeles, Marco Braunschweiler has for a while now gone to a nearby flower market every week and brought bouquets of lilies back to his studio and laid them out on the floor in their newspaper wrappings to photograph them, transforming the newspapers into a timestamp marking the life of the flowers just as in a ransom video. He then transformed the photos into UV-curable prints, which provide a captivating quality of evanescence as they shimmer while th viewer walks around them, and placed the lilies in a vase and shot a time-lapse video to capture the way the flowers expand and contract with the diurnal movement of the sun and then finally expire. A graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, Braunschweiler has also been running a publishing platform called Golden Age with the artist Martine Syms since 2007, and says that he’s moving into more online publishing, releasing singular essays from artists, writers, and thinkers between 5,000 and 30,000 words long. Both his video and photographs were $1,500 each.

Art Picks: Activism Through Flowers, and Pop Culture Clips

Wed, Jan 7, 2015 at 3:54 AM

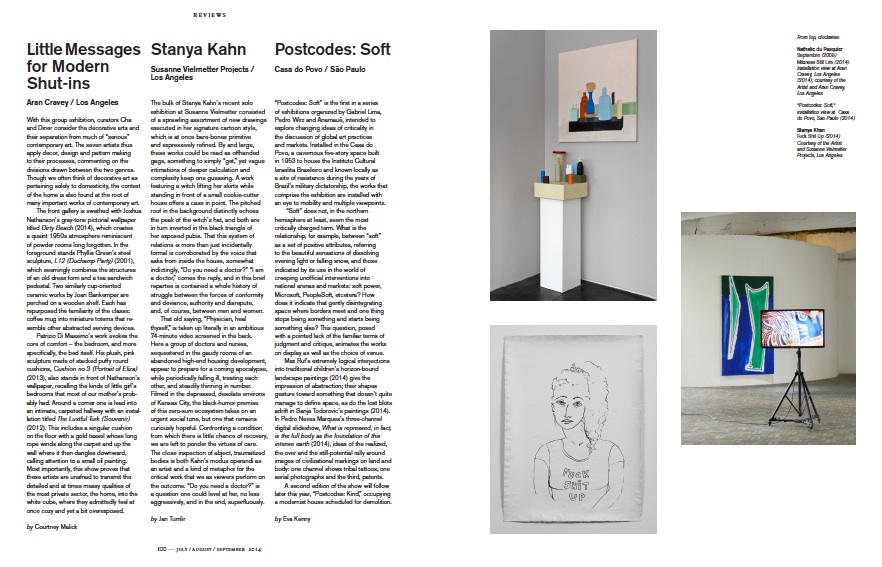

2. Flickering screens

In “Rhetoric,” the current show at Aran Cravey, snippets of commercials and sitcoms flicker across the HD TV that Martine Syms, who refers to herself as a conceptual entrepreneur rather than an artist, installed on two poles at the center of the main room. In the adjacent room, Jibade-Khalil Huffman has layered clips from feature films, projecting them on an angled partition and two parts of the longest wall. Novelist-essayist James Baldwin lectures in a film by Marco Braunschweiler in the small back screening room. Only Baldwin’s white silhouette is visible against the pitch-black background. Intellectualism and pop mingle throughout the exhibition, and the screen vacillates between disorienting and seductive.

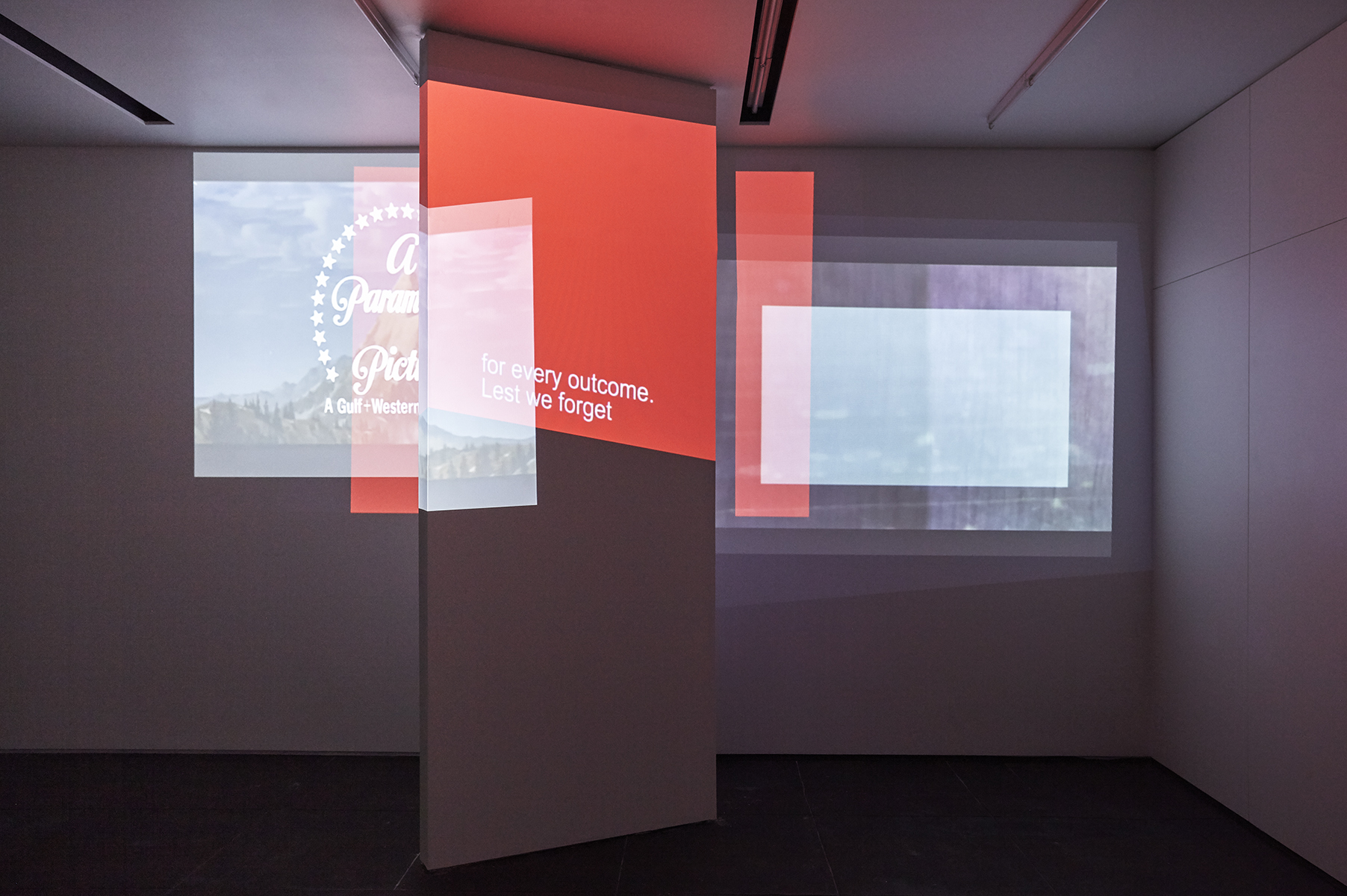

Reviews In Brief, “And Yes, I Even Remember You”

Modern Painters, November, 2014

By David Morton

Human Resources director Eric Kim curates this show that investigates relations between history and memory. In works by Scott Benzel, Patricia Fernández, Hailey Loman, D’Ette Nogle, and Mungo Thompson, material culture acts as a conduit for collective memory. Thompson’s “Inclusion” series from 2014 – small sculptures comprising magazine pages suspended in Lucite – speaks to the way the past becomes inaccessible. Archaeological specimens, advertising logos, and editorial spreads become relics, making change perceivable but remaining impervious to it.

Brief but potent memory: 'And yes, I even remember you' at Aran Cravey

By SHARON MIZOTA

AUGUST 22, 2014

The group exhibition “And yes, I even remember you” at Aran Cravey purports to look at the various ways in which history is created and preserved — a big topic for a small show.

Curated by Eric Kim, it features mostly sculptural works by five artists: Scott Benzel, Patricia Fernández, Hailey Loman, D’Ette Nogle and Mungo Thomson. Kim’s restraint is commendable — there’s no shortage of artists who deal with these issues — and the exhibition has several high points.

Surprisingly interesting is Thomson’s simple gesture of encasing vintage magazine pages in clear Lucite. As you walk around these miniature monoliths, one side is eerily reflected alongside its opposite. A moment in time — literally the turn of a page — is suspended like a fossil in ice.

The artifacts of Fernández’s long-running personal investigation into migrations between Spain and France after the Spanish Civil War make more sense here on simple tables and shelves than they have in more elaborate installations. The objects — small paintings, souvenirs and texts — have a highly intimate quality that draws one into a mysterious narrative, equal parts history and diary.

Even more fugitive is a statement describing a performance by Nogle, in which she vows to attend every social event on curator Kim’s calendar during the exhibition. It suggests a kind of doubling of memory that could be the foundation of any historical record.

In the Spirit of Summer Memories

by Alicia Eler on August 22, 2014

LOS ANGELES — The summer months are a time of slowing down, going out, hitting the beach, and drinking far too many iced coffee beverages. And yes, I even remember you., a five-person group show at Aran Cravey Gallery curated by Eric Kim, wraps up the summer season nicely, reminding visitors of the slippery line between personal stories and broader histories. Are there dominant cultural narratives today, or do we each create and reinforce our own through personal experiences and filter bubbles?

Scott Benzel’s large-scale sculpture dominates the front of the gallery, greeting viewers upon entrance like a beefy bouncer at a club. In “Magnified/Erased” (2014), Benzel revisits American musician Neil Young’s nostril as seen in The Last Waltz (1978), a documentary made by Martin Scorsese about The Band’s last concert. It’s now a well-documented fact that when Young came onstage to sing “Helpless,” he forgot to clean up the traces of his pre-performance coke habits. Later, Scorsese had to pay big bucks to clean up the screen version of Young’s nose, joking that it was “the most expensive cocaine I’ve ever bought.” In Benzel’s piece, he slows down and zooms in on Young’s nose in the film; behind the video loop hangs a blown-up photograph of a flake of cocaine. Two American legends up-close and personal — drugs and rock stars — reveal that living on stardust isn’t sustainable or pretty. Here we see the cloak of fame overturned; no one can maintain appearances forever — not even pop itself.

Benzel adds to this theme of spiritual deficiencies with “L’Affaire de La Chasse spirituelle” (2014), a collection of “stolen” books. One of them, Famous All Over Town, a story about a Mexican- American guy growing up in LA, was written by author Daniel Lewis James but published under the pseudonym Danny Santiago. The Latino name led readers to interpret the book as partial autobiography, but the truth is that Santiago is really James, a white man who wrote as a Chicano. How much does that knowledge affect our reading of the text? It’s up to each individual to decide. A woman named Dania Sanchez, reviewing All Over Town on Amazon, wrote: “I’m not disappointed to learn the Danny Santiago is really Danny James. I’m actually pleasantly surprised that a Caucasian can capture the Chicano way of life so realistically.” Benzel’s piece questions how much “real” personal history matters when communicating a larger cultural narrative.

Hailey Loman imagines memorials for Jewish cemeteries in Los Angeles and Cape Cod, creating minimalist sculptural landscapes of each. Like an elongated, non-functional casket, “Hillside Memorial” (2014) rests on the cold cement gallery floor, sealed shut by a long piece of black plastic with the cemetery’s name inscribed into it in gold. A stack of white sheets, entitled “Hillside Memorial Text” (2014), rests in an archival box next to the memorial, offering viewers a chance to read text-only, deaestheticized versions of newspaper articles such as “Jewish Dead Lie Forgotten in East L.A. Graves” from the March 28, 2013, issue of the LA Times. Rather than standing up or sitting to read these sheets of paper, one must kneel down and slip them out of their box, examining them like found documents or artifacts.

The two collections of materials toward the back of the gallery also have a more archival quality, although less free-form. Mungo Thomson’s and Patricia Fernández’s sculptural installations suggest artist-as-amateur-archivist or vice versa. Fernández’s “Points of Departure (between Spain and France): Port Bou-Cerbere-Bordeaux” (2012) offers a group of materials she collected during this trip in search of familial history. In Thomson’s series, Inclusion, we see pages snipped from magazines and other sources, which the artist has embedded in lucite and placed atop pedestals as if to make them glow. At the end of the hallway, where the majority of them are lined up, we’re greeted with a black text on a white background that simply states “THE COSMOS”; on the other side is a clear image of the stars, memorialized deep inside this thick material. Although they take different approaches, both Thomson and Fernández blend the personal and the cultural, creating a new type of hybrid narrative in the process.

For the last piece in the show, artist D’Ette Nogle has been following curator Eric Kim as he goes about his busy social calendar. Their social engagement began with the opening of the exhibition, on July 18, and ends when it ends, on August 30. The job of a contemporary art curator often involves being an extrovert who enjoys schmoozing, small talk, and meaningful eye contact; this isn’t always the case for artists. Through this effective piece, Nogle reveals both the idea of the curator and the curator himself. At times she’s also made actual social interactions difficult for Kim, unless the conversation veers onto the topic of performance and public engagement. When this happens, the narrative shifts again, raising questions about the difference between performance art and performative art-world social interactions.

5 Artsy Things to Do in L.A. This Week, Including Neil Young's Nose

Wed, Aug 20, 2014 at 5:07 AM

By Catherine Wagley

This week, an obelisk gets covered in handmade bricks, and an artist looks closely at whether Neil Young did or did not have a coke flake on his nose.

4. Where's the coke?

There's a story, reported in memoirs and elsewhere, that in 1976, when Martin Scorsese filmed The Band's farewell concert, Neil Young played his hit "Helpless" with a rock of cocaine in his nostril. A drawn-out effort purportedly followed to edit this cocaine out of Scorsese's documentary The Last Waltz Magnified / Erased (2014) . Artist Scott Benzel's installation includes a big, black-and-white image of a cocaine flake blown up to impossible proportions, with a small TV monitor on a cart in front of it playing zoomed-in footage of Young's nose. Something's happening in and around that nose, but it's hard to tell what. The installation is one of the highlights in the genuinely elegant show about history as myth, curated by Eric Kim at Aran Cravey gallery.

A Group Exhibition Curated by Marisa Olson and Featuring: Conor Backman, Petra Cortright, Alexandra Gorczynski, Marc Horowitz, Christine Sun Kim, Mehreen Murtaza, Jayson Musson, Bunny Rogers, Travess Smalley, Jasper Spicero, Artie Vierkant. ”Raster Raster” includes variant work from painting, sculpture, and textiles to videoembedded digital prints, lenticular images of SecondLife self portraits, and a sitespecific installation by Jasper Spicero featuring the artist’s music and Read More...

Art After the Internet

by Abe Ahn on March 10, 2014

LOS ANGELES — Much of contemporary life is spent behind a screen for work and leisure, with a great amount of time devoted to forming identities and communities through the internet. The young artists of Raster Raster, at the Aran Cravey Gallery, are acutely aware of the shrinking divide between the physical and digital worlds, and they don’t need Google Glass to interface with virtual/IRL experiences and unsettle the dichotomy between the digital and the “real.”

The group exhibition is comprised of artists, the majority in their twenties, who are savvy to digital tools, vernaculars, and memes. They are not afraid to explore concepts and forms once confined to the internet and to draw from their private experience as a means of translation. Not all of the artists fit neatly into the category of “post-internet” art as coined by artist and exhibition curator Marisa Olson, but each of them render, or “rasterize,” the digital age as experienced today.

Artists’ studio practices are increasingly split between digital and physical spaces, as recent work by painters working with digital and analogue mediums can attest. Petra Cortright’s “psxvideo username password SARA homepage” (2013) presents a digital painting on silk, hung slack from its top corners. The soft, translucent brush strokes of the painting billow across the fabric in ways a hard, angular screen could not render.

Alexandra Gorczynski’s “Loops” makes its material origins more explicit by combining painting, photography, and video to form an image of a flowery wreath, a part of which is segmented by a looping video image. Another set of digital paintings, by Travess Smalley, blend computer graphics and physical collage as a study in forms and shapes inspired by Alexander Calder — modernist painting with a digital sheen.

Drawing from imagination, the highly stylized “Triptych” (2009) by Mehreen Murtaza portrays a dystopian future or acid dream in which man and machine are wired to a techno-futurist godhead, while Jasper Spicero’s “Way to Dawn” (2013) brings fantasy to reality by way of 3D printing, mounting a pair of life-size reproductions of weapons from the video game Kingdom Hearts. Both artists channel the destructive or creative possibilities of a networked world in which the biological and material conditions of existence are forever transformed.

Bunny Rogers’ untitled lenticular prints, screenshots of Second Life avatars in various stages of undress or sexual repose, capture nascent sexuality as discovered by a young woman. Propped against a corner of the gallery is a lone mop with a pink ribbon, titled “Self-portrait (mourning mop),” that alludes to Rogers’ internet archive of ribbons and elegizes — by way of personal metaphor — a distant past or identity. These works serve as journals or mementos of private adolescent moments as lived out in the very public setting of the internet.

Not all of the works fit the mold of “post-internet” art, but they are similarly interested in communicating across mediums and between audiences. Christine Sun Kim’s charcoal drawings “All. Day.” and “All. Night.” trace the physical gestures of American Sign Language, along with musical notations, to express in symbols the incommunicable experience of being deaf. Symbols, or cymbals, compose a visual pun in Conor Backman’s semiotic puzzles, and Artie Vierkant’s “Air filter and method of constructing same” complicates notions of proprietorship and intellectual property through its reappropriation of a patented invention as a work of art.

Also featured are Marc Horowitz, most famous for his itinerant culture jamming and crowdsourced performance art, with a digital c-print “The One That Could Have Been,” and painter-turned-YouTube-wit Jayson Musson, known for his ART THOUGHTZ critiques carried out as alter ego Hennessy Youngman. Both artists playfully undermine mass media consumption and art world pretense, with the latter breaking down in eloquent and plainspoken vernacular the smoke and mirrors of International Art English.

All of these works can exist in the space of a gallery or museum, but they mostly reside in the space of a screen, reproduced here and elsewhere. The way most people will experience them will be through a digital interface, which cannot recreate color, scale, and texture as perceived in “real life.” For many of these artists, this is a necessary limitation, but it also enlarges the possibilities of how people may perceive, experience, and preserve the work of artists in the near future.

Raster Raster continues at the Aran Cravey Gallery (6918 Melrose Avenue, Los Angeles) through April 12.

Are you familiar with the term "postinternet art"? If not, allow us to introduce the terminology to your art vocabulary. First used by artistMarisa Olson, the phrase refers to artworks made in the age of the internet that simultaneously celebrates and criticizes its online fruits. Designs, memes, trends and the politics of the web collide in this novel categorization of 21st century artists.

A new exhibition entitled "Raster Raster," curated by Olson, combines many of the key players in the postinternet art movement, from webcam-happy Petra Cortright to satirical YouTube sensation Jayson Musson. The exhibition title riffs off the graphic design term "rasterize," which means to scan and output an image, while toying with the sounds of "faster, faster!" speaking to the frantic pace of technology and art making.

The multifarious exhibition includes paintings, sculpture and textiles, along with some more unorthodox media like Second Life self portraits, 3D printed sculpture and digital paintings on silk. "This is work that one might call 'art after the internet’" explains Aran Cravey Gallery in a statement. "That is, work that simultaneously enjoys and critiques the internet, responding to and incorporating its tropes, memes, cultural politics, and visual language into forms that may or may not live online. 'Raster Raster' plays to the synesthesia of visual culture that the internet makes use of; a modern pictorial language that interchanges words with ‘real’ and fictional imagery."

See a preview of the works below and take note, here are six postinternet artists you should know.

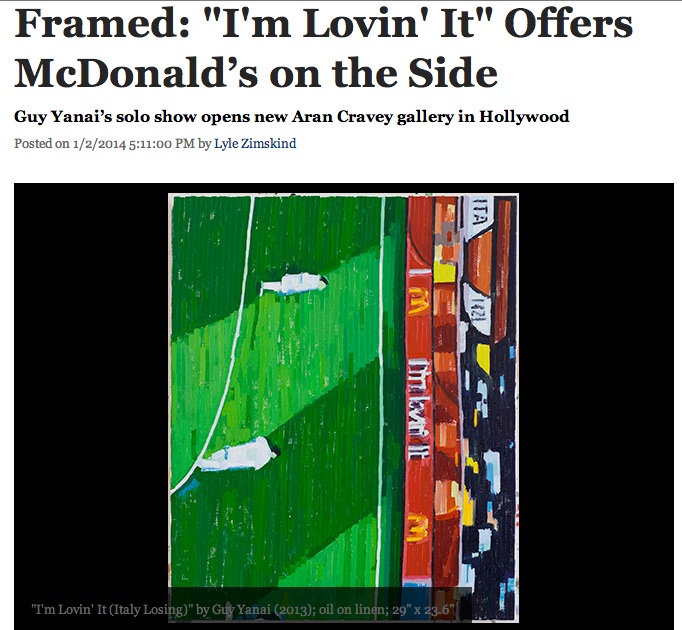

The midfield vantage point on the soccer match in Tel Aviv-based artist Guy Yanai’s painting “I’m Lovin’ It (Italy Loses)” is an angle instantly familiar from television broadcasts of sporting events. Hardly less prominent than the players or the field, the sideline wall in the background features an all-too-recognizable image of McDonald’s Golden Arches and the accompanying slogan “I’m Lovin’ It.” Though there is a real athletic contest going on (one destined to disappoint any Gli Azzurri diehards), the action of the game as presented here gets subsumed by the communications media surrounding it.

The attentive viewer of this work, as well as five of the other 17 oil paintings in Yanai’sAccident Nothing exhibition at the new Aran Cravey Gallery space in Hollywood, will also notice that these images are hanging sideways.

The White House in Washington D.C., a Stockholm street, the Great Pyramids of Egypt, an Israeli kibbutz’s guest quarters, and a Hockney-inspired backyard swimming pool—all of these scenes are rendered, like “I’m Lovin’ It,” as bright icons of a distant part of the world, each viewable in its rectangular frame as though you're looking through a window or a broadcast screen. Yanai himself, we are informed, painted all these images horizontally from what we might colloquially call a “right side up” perspective. But the pictures were then purposefully turned 90 degrees before they were ready to be displayed to the world.

Half of the works in Accident Nothing comprise the series of “Nothing” paintings—nine small, square (non-sideways) tableaux featuring vividly colored geometric shapes, some arranged in representations of simple images like an awning, a cinema projection or a croquet pole while others are expressly abstract. The paintings in this set all radiate a dynamic stillness, suggesting a warm and compelling place distinguished by nothing happening.

Every one of the works on view in Accident Nothing, including three large, context-free portraits of trees, features a distinctively striated brushstroke. It's as if the paint had been applied with long parallel strips of tape or a sharp-edged tool. In fact, the highly visible stripes that stretch over long expanses of each painting surface testify to the hypnotic meticulousness of the artist’s technique, a contemplative state that anyone encountering these works may get drawn into.

As Resort 2014's show season wraps up, a number of collections have emerged with distinct ties to the art world – from mega-brands to smaller indie labels.

Calvin Klein’s womenswear creative director,Francisco Costa, sought inspiration — albeit obtuse — from the pop-bright minimalist Ellsworth Kelly. Costa reportedly became smitten with the colors he observed during a visit to Kelly’s studio, which explains the atypically bold hues he used on otherwise minimally dyed garments.

Scott Sternberg, the California whiz kid behind Band of Outsiders, tapped Israeli artist Guy Yenai, himself inspired by David Hockney's "A Bigger Splash," for a series of geo-abstract prints depicting a blockier sort of Beverly Hills midcentury idyll across BOO’s sporty tops and dresses.

Reed Krakoff looked to Robert Motherwell’s “Open” series – namely drawing from the washed-out palette of sage blue and sunbaked tan, and its repeated cubic motifs (for example, the designer laser-etched squares across leather tops, in the aforementioned cyan). Krakoff, a big-time collector, oft seeks to blend fashion and visual art in his designs.

Over at Sportmax, MaxMara’s younger and, yes, more athletic line, the silhouettes sprang from Ron Jude’s “Executive Model” series. In the photographs, Jude lensed larger-than-life Wall Street types in suits, vaguely in line with Robert Longo’s exploration of the finance world.

And lastly, James Turrell informed young Manhattan designer Misha Nonoo’s saturated, ombré moments in her cheery lineup, recalling the gradients often seen in the light artist’s immersive work.